(At this point I'm going to take some more artistic license, and change the narrative voice a bit. Instead of trying to write fictional dry history, I thought it might read better if this read like more of an oral history. If this doesn't work out, I'll switch back!)

November 14, 1957

"You're going to break our phone if you slam it like that again, Charles."

Von Braun's tone was humorous, but it also barely concealed the German's apprehension about something as trivial as weather conditions 800 miles south of them.

"Yes, well." Charles Hutchinson had been on the job less than 3 months and was unaccustomed to dealing helplessly without variables like weather. While the other men gathered around in the Pentagon War Room were veterans of various test-firings and had made do with weather variables, this was Hutchinson's first launch, and there was no "test" about it. "I think there are some Air Force meteorologists who will be making Hutchinson Voodoo dolls at any rate." He drummed his fingers absently on the phone, and then looked around the table at the 6 men gathereed there. "No change really, and in fact it sounds like it could be getting worse. Wind steady at 15-18 knots, gusting to 20-25."

"So no launch this afternoon?" James Van Allen--the designer of the instruments to be carried aloft by the rocket that stood on a wind-buffeted platform in Florida--was also present. If the others there held varying degrees of fascination regarding rocketry and space travel, Van Allen was the exception. He thought of rockets as little more than tools to get his measuring devices higher and higher into the atmosphere; for him the rockets were the weak link in the process and always would be.

Hutchinson turned to Van Allen. "No. Not this afternoon. I'm sorry Jim."

"How long do they expect these weather conditions?" Von Braun asked.

"Well, heavy winds through the early afternoon, but then hopefully dying down by nightfall. But then they're expecting some kind of rain squall. Tonight. Maybe all night."

"So the rain may be heavy?" Von Braun looked concerned. "If this is the case, we will want to get the rocket off the platform."

"I'd have given them your order, Doctor. Apparently there are a couple of folks down there who feel like there may be a good 2-hour window around 10 tonight."

Von Braun stood up and began to pace around the room. "I wonder what kind of weather they are having in Russia right now."

Hutchinson smiled in spite of himself "Probably unseasonably warm, dry, and no winds."

The fledgling Space Agency had been under enormous pressure of late. CIA intercepts and a couple of spy plane flyovers had not only confirmed that there were 5 Soviet launch sites in a decent cluster around central Russia, but also that the Soviets had already attempted two launches to put a satellite in orbit around the earth. The first had apparently blown up in the sky before it could fire it's second stage. The second had flown well, if the CIA could be believed...but the satellite had failed to make a good orbital burn and and came apart in the upper atmosphere. Von Braun and the others knew that a succesful Soviet satellite launch was only weeks, maybe days away, and they were racing against time.

Not that the launch at Cape Canaveral carried any guarantees with it. Far from it. NASA, now coming up on it's second birthday, was still a bureaucratic mess. Under pressure from Ike and Congress to put a satellite up within a year, the first NASA director would be forced to choose between two sons. The Navy had been working on a rocket and satellite combination called Vanguard which they hoped to launch by mid-1956. The Army had pushed for NASA to go forward with the modified Redstone/Jupiter/Atlas rockets they had been developing with "Our Germans" at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency in Huntsville, AL.

The ABMA in Alabama was "officially" an arm of the US Army, and thus the primary concern was developing reliable long-range ballistic missiles. Spearheaded by the German rocket scientists captured by the United States in the fall of the Third Reich, these scientists had little interest in the use of their rocket technology for weapons, but rather they secretly developed launch platforms that could carry heavier and heavier weights farther and farther with the idea of using their inventions to explore outer space. Headed by Romanian theorist and Goddard contemporary Hermann Oberth and brilliant young German Werner Von Braun, the ABMA physicists were almost as sure that their rockets would fly as they were that the Navy's Vanguard rockets would not.

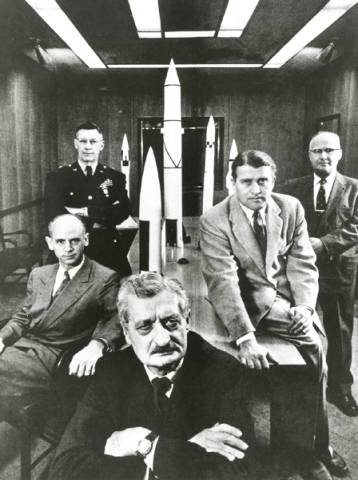

(The ABMA group at Hunsville, consisting of "Our Germans" as Eisenhower had dubbed them. Hermann Oberth is in the foreground, with Wernher Von Braun seated on the table to his left.)

Imaginably there was tremendous rivalry between the Army and Navy for NASA's green light and funding for a launch, and when NASA chose the Navy's Vanguard program, the ABMA could have gone into hibernation. Vanguard was officially selected because, according to NASA, it was the more "feature complete" program; indeed, the Naval Research Laboratory promised that if NASA made their program the focus for the first satellite to be launched into space, they could be ready for a launch by October, 1956. The unspoken reason for choosing the Navy's rocket and satellite was due more to the lineage of the rockets. Vanguard was seen as the "All-American" rocket--built and developed by US scientists, while within the halls of Washington, there was concern that a layer of old Nazi Germany hung over the rocket science going on in Huntsville.

So, NASA backed Vanguard, making the announcement officially in March of 1956, but unofficially told the ABMA at Huntsville to continue their work simply as a contingency should Vanguard encounter problems. Von Braun and his crew had every intention of doing so anyway, because as the German told his colleagues, "Vanguard will not fly."

Early on, Von Braun seemed to be right. Hopes for an October, 1956 launch were scuttled by a steady stream of unsuccessful test firings of NASA and the Navy's rocket. Then in early summer of 1957, the New York Times broke the news that the launch of a Soviet satellite, called Sputnik, was imminent. "Sputnik Fever" gripped the country, suddenly caught up in the fervor of a "Space Race", as a Collier's Magazine story had put it. There were Sputnik science fiction stories, Sputnik songs, and even talk of a Sputnik movie wherein the evil Soviet satellite launched an invasion of earth, only to be repelled by the bravery of the United States armed forces.

NASA announced on June 21st that the kinks had been worked out of Vanguard, and the rocket and satellite were ready to fly. The launch date was set for July 4, and NASA promised a "rather memorable fireworks display" for the American public that day.

(Vanguard I on the launch pad, July 2nd 1957. Two days later it would be the first launch under the supervision of the newly created NASA.)

[/i]

With the launch site--Cape Canaveral in Florida--crawling with Washington politicians, military brass, hundreds of press, and perhaps thousands of interested by-standers across the inlet, NASA counted down the final seconds before launch. Listening in on closed-circuit radio transmissions in Huntsville, Von Braun is alleged to have said to a colleague "If this thing flies, I'll eat my feet."

Moments later, the initial stage for Vanguard ignited with a roar and great billowing clouds of fire to the "oohs" and "ahs" of awed spectators. It lifted itself from the platform and immediately zoomed to its maximum altitude--in this case, four feet. Then the first stage engine exploded, the entire rocket collapsed in upon itself, and the remaining fuel in the secondary and orbital stages ignited as well forming a huge, oily, fiery explosion that seemed to observers to have been some sort of bad joke.

The unsuccessful launch of Vanguard I on July 4, 1957.

The headlines the next day in the paper made NASA the butt of a national and worldwide joke. "KAPUTNIK", "STAYPUTNIK", and "FLOPNIK" were some of the more wickedly funny headlines conjured up by angry newspaper editors who felt, like many Americans, betrayed by the level of readiness they'd been led to expect from the Space Administration prior to launch.

With mass resignation at NASA and talk of massive funding cuts (not to mention a palpable sense of growing panic that America had not only lost the Space Race already, and perhaps the Cold War in the bargain) Von Braun and the ABMA stepped into the breach. While Vanguard was undergoing numerous unsuccessful tests, the Huntsville crew had managed numerous successful launches of a modified Redstone/Jupiter ballistic missile which Von Braun felt could be further modified to provide the lift required to put a satellite into orbit.

NASA had learned from its Vanguard error, and that's where Hutchinson came in. He'd arranged for the rocket assembly and it's precious payload to be secretly shipped into the Cape as soon as Von Braun told him the new ABMA rocket, tentatively dubbed "Atlas" was ready. Although Hutchinson had encountered more residual doubt about this rocket from his NASA peers, he had faith in Von Braun's acumen.

What he didn't have faith in was the payload. In a very early meeting, Hutchinson had sat down with Von Braun and William Pickering of the Jet Propulsion Lab, the latter group being the one to design the actual "artificial moon"--the satellite that would theoretically be put into orbit. Pickering was angry. The JPL had been given no warning by the NRL, and the Vanguard satellite component was merely a radio transmitter with antennae.

"Well Bill," said Hutchinson, "isn't that basically what Sputnik is going to be when the Russians put it up?"

Pickering snorted. "Yes, we can make a satellite that's no better or worse than something the Kremlin could dream up. Is that what we want? I'll be frank, gentlemen. The American scientific community is apoplectic about this little radio beeper you want to launch. Give us a few weeks--a month even--and we can deliver you a satellite that will perform honest-to-god measurements and data collection up there. It'll give the launch some scientific purpose!"

Hutchinson had heard this before. Von Braun expressed their mutual opinion "Can we not do the science on a subsequent launch? Should we not find out whether we can do this first?"

"We can do this--we'll put a satellite up there eventually, fellows. If not this year, then next. It will work. But I assume you don't plan to stop there. If you're going to try a manned space program--and everyone knows you are--you'd better start collecting data right away. For instance, you have to know what sort of radiation you're dealing with on cosmic rays."

The phrase "cosmic rays" meant one thing to Von Braun and Hutchinson. An Iowa physicist named James Van Allen had been launching small rockets from high-altitude observation balloons for over a year now, each rocket equipped with tiny, lightweight geiger counters. Van Allen had observed that as the atmosphere thinned at its highest altitudes, there seemed to be a buildup radiation from the sun and outerspace, something he called "cosmic rays".

"Van Allen got to you, eh Bill?" said Hutchinson with a laugh.

"Well, yeah. But the man is right. If he can put a tiny radiation sensor into one of his rockets, surely we can do something like it with regards to a satellite. And we can

do this gentlemen. It isn't a matter of months or years before we can build this satellite! It's a matter of days. We could have one ready to go by mid-October!"

In the end, Hutchinson and Von Braun had given Pickering and Van Allen a go. The Explorer satellite, as it was designated, would be a modified Sergeant rocket in two sections. The rear section was a small rocket engine that would be used to put the satellite into it's orbital path when it exited the atmosphere. The front section contained 3 instruments, including a thermometer and Van Allen's "Cosmic Ray" device--a super geiger counter to measure the radiation swirling about the outside of the atmospheric protection. Finally, Explorer would contain two separate radio transmitters to beam the signals from the instruments back to Earth.

Everything had shipped into the Cape in good shape. The Juno/Atlas rocket stood on the launch platform, with Explorer I ready to go as its payload. Now the weather would need to cooperate. Hutchinson, Von Braun, Van Allen, Pickering, and a host of Army brass sat around the War Room at the Pentagon waiting to hear from counterparts at The Cape. The group had sent out for an early dinner and was in the middle of it--5 pm local time--when the secure line phone rang again. Von Braun and the others saw no change in Hutchinson's expression as he answered a few questions with terse "yesses", "no's", and a final "we'll get right back to you," as he hung up the phone.

"Well?" Von Braun was standing.

Hutchinson smiled. "Winds down to 8-12 knots, and falling. We can be go for a launch by 8:30. No rain until after midnight. If that's enough time, Herr Doctor, I can give them the go-ahead."

Von Braun sat back down. "It is not ideal, but such things seldom are. If the Soviets beat us because of a thunderstorm, it will not be a good thing. We will have to go sometime. I say we do so now."

Hutchinson made the call. Launch time was officially set: 8:40 pm.

With the rocket and platform bathed in the light of dozens of floodlights, the crew at the Cape went through the final preparations for launch. Although the launch was "secret", word had gotten out, and over the past day a small crowd had gathered at the nearby beach to watch--enough people that a few police cruisers were required to keep the peace. In addition, there were a handful of press present, although they had been forced to agree to "embargo" their stories on the launch until the next day.

(Explorer I atop an Atlas/Juno rocket, lifts off to put the first satellite in space on November 14, 1957.)

Hutchinson and his crew sat inside the War Room and watched as a clock ticked by. 8:40 came and went. The phone rang. Hutchinson couldn't hide his relief from the others in the room.

"Atlas cleared the platform and is on the way! It appears that both stages have fired perfectly!"

The room exploded into cheers but Hutchinson, beaming himself, tried to calm everyone. "We expect our first signal response in 2 hours. Then we'll know if we have a satellite or not."

The next two hours were spent guzzling coffee and engaging in quiet but anxious conversation. Occasionally Hutchinson would call the Cape. No new news. 10:45 came and went. Shortly before 11, the phone rang.

"Then why did you call me?" asked Hutchinson angrily into the receiver. He crossed his arms. "Cape called to say they haven't heard anything yet. We may have missed on the orbital burn."

Pickering, who had pushed hard for the Explorer configuration that went up earlier that evening, was unmoved. "She's a good machine. Give her a chance."

When the phone rang again after midnight, the men in the room were expecting the worst.

"You're sure?" said Hutchinson. His face broke into a broad grin. "That's fantastic news!" By the time he'd hung up, everyone else was standing and looking at him expectantly.

"We have a signal. We have a satellite!" The room exploded into cheers and backslapping. The space age had begun.

"Anything on the signal delay?" Pickering wanted to know.

"Yeah, apparently we managed an orbit almost a hundred miles higher than we expected. But it is a beautiful orbit, and we're getting radio like crazy from Explorer right now."

Someone had come up with a bottle of champagne and the men imbibed as they shared congratulations. Now Hutchinson had a surprise for the room. "Dr. Von Braun, Mr. Van Allen, Mr. Pickering?"

The men paused in their mutual congratulatory merrymaking.

"There's an Army car waiting for you. There are some gentlemen from the press at the National Academy of Science who'd like to ask you some questions. Congratulations fellows. Here's to many more launches just like this one!"

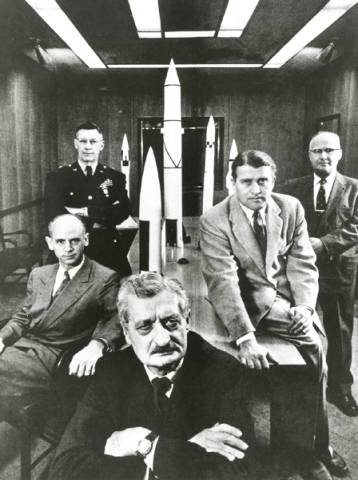

(l-r William H. Pickering, James Van Allen, and Wernher Von Braun celebrate at the press conference at the National Academy of Science with a full-scale model of Explorer I)

(l-r William H. Pickering, James Van Allen, and Wernher Von Braun celebrate at the press conference at the National Academy of Science with a full-scale model of Explorer I)"It's my manner, sir. It looks insubordinate, but it isn't, really."

[/i]

[/i]